Burning of books and burying of scholars

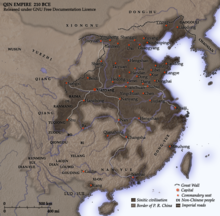

Qin Empire in 210 BCE

Qin region Outlying regions |

| Burning of books and burying of scholars | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 焚書坑儒 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 焚书坑儒 | ||

|

|||

Recent scholars doubt the details of the story in the Records of the Grand Historian—the main source —since Sima Qian, the author, wrote a century or so after the events and was an official of the Han dynasty, which could be expected to portray the previous rulers unfavorably. While it is clear that the First Emperor gathered and destroyed many works which he regarded as subversive, two copies of each school were to be preserved in imperial libraries. These were destroyed in the fighting following the fall of the dynasty. It is now believed that there likely was an incident, but they were not Confucians and were not "buried alive."

Fajia (Chinese: 法家; pinyin: Fǎjiā)[2] or Legalism is one of Sima Tan's six classical schools of thought in Chinese philosophy. Roughly meaning "house of Fa" (administrative "methods" or "standards"),[3] the "school" (term) represents some several branches of realistic statesmen[4] or "men of methods" (fashu zishi)[5] foundational for the traditional Chinese bureaucratic empire.[6] Compared with Machiavelli,[7] it has often been considered in the Western world as akin to the Realpolitikal thought of ancient China.[8] Largely ignoring morality or questions on how a society ideally should function, they examined contemporary government; emphasizing a realistic consolidation of the wealth and power of autocrat and state, with the goal of achieving increased order, security and stability.[9] Having close ties with the other schools,[10] some would be a major influence on Taoism[11] and Confucianism, and the current remains highly influential in administration, policy and legal practice in China today.[12]

Though Chinese administration cannot be traced to any one person, emphasizing a merit system administrator Shen Buhai (c. 400 BC – c. 337 BC) may have had more influence than any other, and might be considered its founder, if not valuable as a rare pre-modern example of abstract theory of administration. Sinologist Herrlee G. Creel sees in Shen Buhai the "seeds of the civil service examination", and, if one wished to exaggerate, the first political scientist.[13] The correlation between Shen's conception of the inactive (Wu wei) ruler responsible for examination into performance, claims and titles likely also have informed the Taoist conception of the formless Tao (name that cannot be named) that "gives rise to the ten thousand things."[14]

Concerned largely with administrative and sociopolitical innovation, Shang Yang (390–338 BC) was a leading reformer of his time.[15][16] His numerous reforms transformed the peripheral Qin state into a militarily powerful and strongly centralized kingdom. Much of Legalism was "principally the development of certain ideas" that lay behind his reforms, and it was these that helped lead to Qin's ultimate conquest of the other states of China in 221 BC.[17][18]

Shen's most famous successor Han Fei (c. 280 – 233 BC) synthesized the thought of the other "Fa-Jia" in his eponymous text, the Han Feizi. Written around 240 BC, the Han Feizi is commonly thought of as the greatest of all Legalist texts,[17][19] and is believed to contain the first commentaries on the Tao te Ching in history.[20] The grouping together of thinkers that would eventually be dubbed "Fa-Jia" or "Legalists" can be traced to him,[21][22] and The Art of War would seem to incorporate Taoist philosophy of inaction and impartiality, and Legalist punishment and rewards as systematic measures of organization, recalling Han Fei's concepts of power (shih) and tactics (shu).[23] Attracting the attention of the First Emperor,[24] It is often said that succeeding emperors followed the template set by Han Fei.[25]

Calling them the "theorists of the state", sinologist Jacques Gernet considered the Legalists/Fa-Jia to be the most important tradition of the fourth and third centuries BC,[26] the entire period from the Qin dynasty to Tang being characterized by its centralizing tendencies and economic organization of the population by the state.[27] The Han dynasty took over the governmental institutions of the Qin dynasty almost unchanged.[28] Endorsement for the "school" of thought peaked under Mao Zedong, hailed as a "progressive" intellectual current